Categories

The Evolution of Malware

‘Brain’ was the first PC virus, and it appeared in 1986 with two notable features. It took over of the Master Boot Record, controlling the way a computer started even before loading an operating system, a fundamental technique that has returned relatively recently.

And it was designed by two brothers, Amjad and Basit, which we know because in the code they included their names, address, and phone number in Lahore. They’re still at the same address, thirty years later, where they run a successful cyber consultancy.

Brain led to other Master Boot Record viruses, including ‘Stoned’ and its successors. The most famous variation of Stoned was Michelangelo, launched in 1991 and discovered a year later. Michelangelo stood out in three ways.

First, it was silent, the first major malware to be so. It didn’t announce itself with cute graphics, like the CoffeeShop virus of the same year, or the Ambulance Car or Walker man viruses of the same period. Instead, Michelangelo sat and waited, until Michelangelo’s birthday on March 6th, to erase data on infected drives.

Second, Michelangelo became a worldwide concern. In 1992, not only did most people have no protections against malware, they didn’t necessarily believe it existed. Many people thought computer viruses were a hoax concept, peddled by scare-mongers. Michelangelo turned out to infect far fewer computers than expected, but it did raise awareness of vulnerabilities.

And third, it launched the anti-virus industry.

Cybersecurity Begins

In the 1990s, computer security began in earnest.

Anti-virus firms existed before Michelangelo but at a limited scale. In 1991, McAfee had a few dozen employees. In 1992, in the wake of Michelangelo, it went public and raised tens of millions of dollars for its expansion. Norton and Symantec became household names. In the following 25 years, we’ve relied on professional, commercial firms to protect us against attacks, including ‘silent’ ones, like Michelangelo, that do damage without first announcing their presence.

Hackers also evolved. In the 1990s many were kids, like Chen Ing-Hau, who wrote the destructive ‘Chernobyl’ virus, as a student in Taiwan, to prove he could circumvent software security. In 2000, a fifteen-year-old Michael Calce, calling him self ‘Mafiaboy,’ shut down Yahoo! with a denial-of-service attack. The following week, he locked up eBay, Amazon, and CNN. (Calce, sentenced to eight months of custody by the Montreal Youth Court, also now works as a security consultant.)

From 2000 to 2010, hackers became more professional, choosing targets to further financial and political aims.

A few years brought a significant shift. By then, the internet saw more hackers like Tariq Al-Daour, who with malware, stole credit card numbers that enabled broad theft. He laundered the pilfered money through online casinos, then purchased equipment to send to fighters in Iraq. His co-conspirators, and others like them, bridged the gap between lone hackers seeking thrills and state-sponsored cyber-teams.

Sophisticated hackers with financial or political aims were about to proliferate.

Modern Malware

By the next decade, from 2010 to 2020, the landscape had changed again. The range, persistence, and sophistication of malware attacks was entirely different from before.

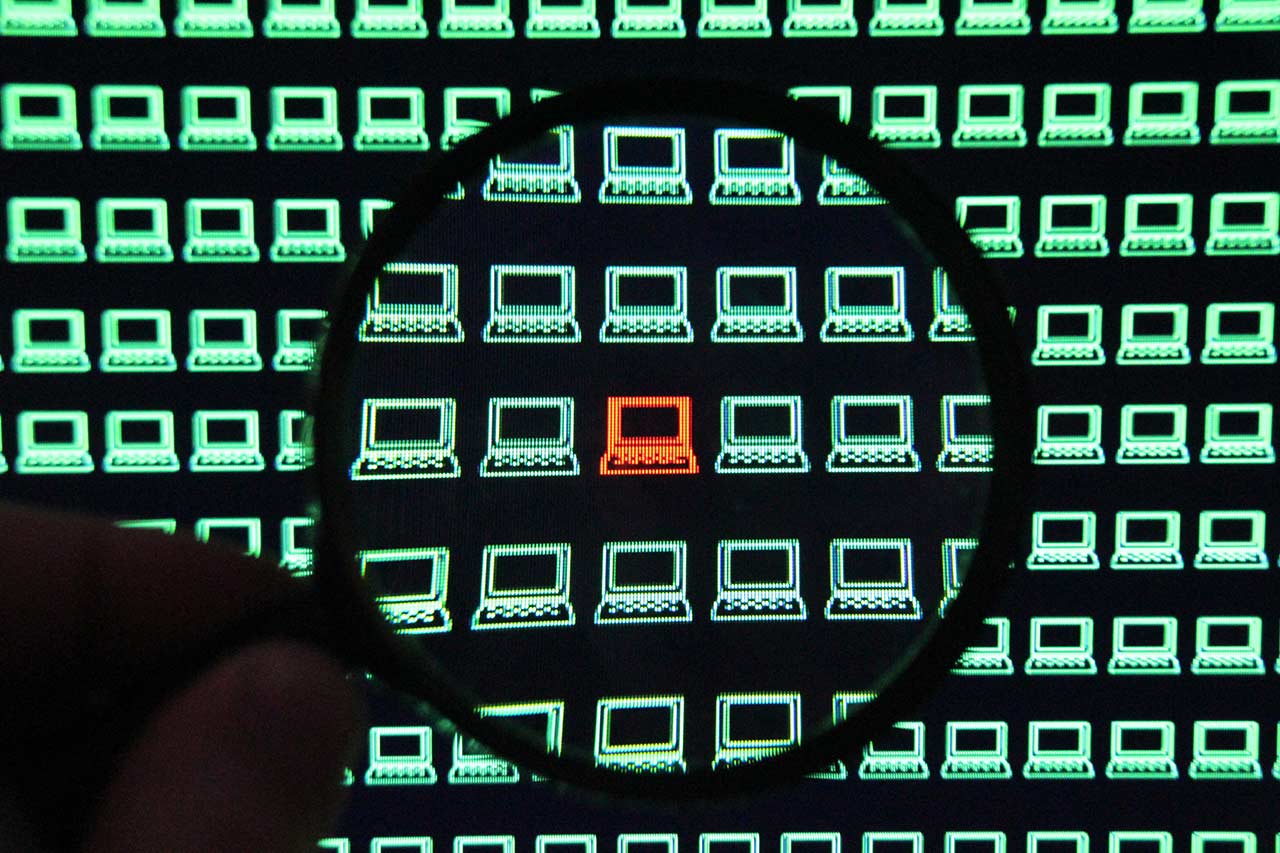

The world now saw endless probing for simple security flaws, through malware written by artificial intelligence programs. AI’s generated streams of new programs searching for exploits, changing their code just enough to avoid detection by existing anti-malware defenses, or to try variations of known attacks. By 2017, internet security firm AV-Test estimated there were 640 million malware programs in circulation.

Anti-malware firms can no longer manually check all threats. In the 1990s, researchers at Norton would read through each line of code in a potential attack to assess its threat and to look for methods of mitigation. Now they, too, employ AI to parse the torrent of new code.

The Modern Landscape of Malware

- There are now more than a billion malware programs.

- An estimated 670 million new malware programs arrived in 2020, according to AV-Test.

- IoT devices provide vast growth in targets. 9.9 billion of them are already connected worldwide.

- Many IoT devices have no malware protections at all. Others rely on firmware protections that are infrequently updated.

- State-sponsored teams of cyber hackers produce new levels of sophisticated, targeted attacks.

In another article, we’ll address the problems of state-sponsored attacks, including new methods of leveraging old techniques from Master Boot Record Attacks. And we’ll look specifically at IoT-targeted attacks. Here, we’d like to highlight the problem of the sheer number of malware programs.

That volume matters. If your software caught 99.99% of the new threats in 2020, then 67,000 would get through. A given agency or firm may have protections that do better, but even if they are better by orders of magnitude, by ten times or a hundred times or a thousand, that is still not enough to secure a system.

PathGuard’s hardware-based design thrives in this new landscape. Its non-diagnostic nature allows it to offer security even against threats that haven’t been identified. Tomorrow, there will be 1.8 million more.